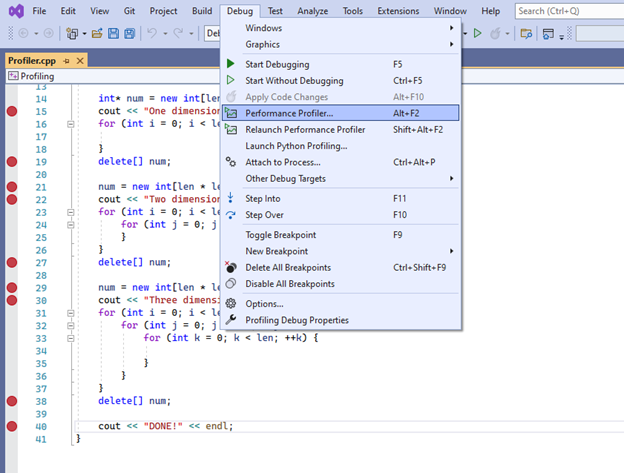

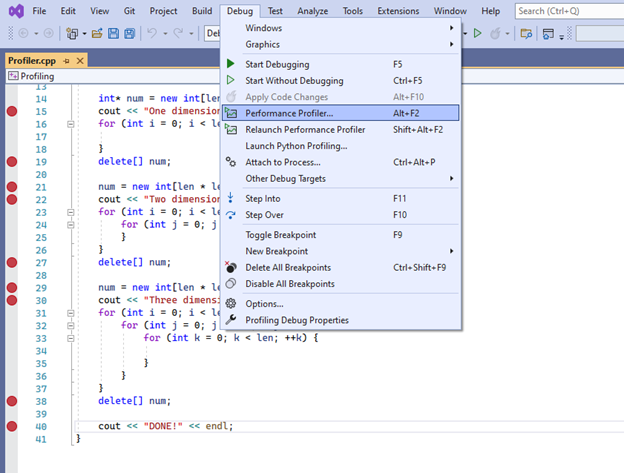

To see this information, click on Debug>>Performance Profiler.

Lecture recording here.

Lab recording here.

To many programmers, development is the heart of software engineering. It's where fingers hit the keyboard and churn out the actual program code of the system. Without development, there is no application. As is the case with other stages of software development, the edges of development are a bit blurry. Low-level design may identify the classes that a program will need, but it may not spell out every method that the classes must provide and it might provide few details about how those methods work. That means the development stage must still include some design work as developers figure out how to build the classes.

| Software Development Environments: | Development Environments and Why You Need One |

| Source Code Control: | What Is Version Control? |

| Software Profilers: | Software profiling and profilers |

| Static Analysis Tools: | What Are Static Analysis Tools? |

| Refactoring Tools: | What is Refactoring? (as a software developer) |

Lab 3: Automated Irrigation System

Lab 4: Stockpicker

Assignment 2: Airline Travel Assistant

Including overhead (office space, computer hardware, network hardware, Internet service provider, vacation, sick time, a well-stocked soda machine, and so forth), employing a programmer can easily cost more than $100,000 per year. A manager should be willing to spend a few hundred bucks for proper programming tools.

Few things are as frustrating as trying to write software on inadequate hardware. Programmers need fast computers with lots of memory and disk space. A programmer with an underpowered computer or insufficient memory takes longer to do everything. Make sure the programmers have all the hardware resources they need to do their jobs quickly and effectively. If that means buying more memory, disk space, or even new computers, do it.

There are two drawbacks to buying the programmers everything they need. First, some programmers will go overboard and buy all sorts of fun toys that they don't actually need. The second and far more important drawback to giving developers everything they want is that they sometimes forget that their users may not have such nice equipment.

There are development groups that don't allow access to external networks. If it's at all possible, you should allow programmers to have free access to the Internet. Often a quick search can find a solution to a programming problem that would otherwise take hours to solve. Perhaps you will have to enact a strict anti-serfing policy to discourage programmers from playing on the internet.

A development environment should at least include the compiler or interpreter that translates program code into something the computer can execute. An integrated development environment ( IDE ) such as Eclipse (mostly for Java, although plug-ins let you write in other languages such as C++ or Ruby) or Visual Studio (for Visual C#, Visual Basic, Visual C++, JavaScript, and C#) can also include much more. Depending on the version you have installed, they can include debuggers, code profilers, class visualization tools, auto-completion when typing code, context-sensitive help, team integration tools, and more.

If your development environment doesn't include source code control, a separate system is essential. A documentation management system is important for letting you track the many documents that make up a project. Source code control is even more important for program code where changing a single character can reduce a working program to a worthless pile of gibberish. A good source code management system enables you to go back through past versions of the software and see exactly what changes were made and when. If a program stops working, you can pull out old versions of the code to see which changes broke the program. After you know exactly what changes were made between the last working version and the first broken one, you can figure out which changes caused the bug and you can fix them. Source code control programs also prevent multiple programmers from tripping over each other as they try to modify the same code at the same time. For more information, see What is a VCS? Overview of Version Control Software.

Profilers let you determine what parts of the program use the most time, memory, files, or other resources. These can save you a huge amount of time when you're trying to tune an application's performance. You may not need to buy every programmer a profiler. Typically, a small part of a program's code determines its overall performance, so you usually don't need to study every line's performance extensively. Still it's important to have profilers available when they are needed. For more information, see the Stackify code profiler.

The following code can be used to demonstrate software profiling, where breakpoints are introduced

where we can take snapshots to see how much CPU time a portion of the code uses, as well as the

growth and reduction of dynamic memory. The code is Profiler.cpp.

To see this information, click on Debug>>Performance Profiler.

Profilers monitor a program as it executes to see how it works. Static analysis tools study code without executing it. They tend to focus on the code's style. For example, they can measure how interconnected different pieces of code are or how complex a piece of code is. They can also calculate statistics that may indicate code quality and maintainability such as the number of comments per line of code and average the number of lines of code per method. For more information see The Best Static Code Analysis Tools.

Some development environments do a better job of formatting code than others. For example, some environments automatically indent source code to show how code is nested in if-then statements and loops. That formatting makes code easier to read and understand. That in turn reduces the number of bugs in the code and makes finding and fixing bugs easier.

The term refactoring is programmer-speak for "rearranging code to make it easier to understand, more maintainable, or generally better." Some refactoring tools (which may be built into the IDE) let you do things like easily define new classes or methods, or extract a chunk of code into a new method. Refactoring tools can be particularly useful if you're managing existing code (as opposed to writing new code). For more information see The Complete Engineer's Guide to Code Refactoring.

How would you refactor the following code: Report.cpp?

See PrintReport.cpp for an answer.

This is another category where some managers are penny-wise and pound-foolish. Training makes programmers more effective and keeps them happy. A few thousand dollars spent on training can greatly improve performance and help you retain your staff. Online video training courses and books are often less effective than in-person training, but they're also a lot less expensive and they let you study whenever you have the time. If a $50 book gives you a single new tip, then it's probably worth it.

After low-level design is mostly complete (and you have all your tools in place), you should have a good sense of what classes you need and the tasks those classes need to perform. The next step is writing the code to perform those tasks. For more complicated problems, the first step is researching possible algorithms. An algorithm is like a recipe for solving a hard programming problem. In the decades since computers were invented, many efficient algorithms have been developed to solve problems such as the following:

Note that some algorithms may be efficient enough for one purpose but not for another. When comparing algorithms, we often look at the worse case scenario. The worse case scenario might not be likely, therefore comparisons have to sometimes consider the most likely scenario. Also, the performance of algorithms will vary according to data size.

In top-down design for software development, you start with a high-level statement of a problem, and you break the problem down into more detailed pieces. Next, you examine the pieces and break any that are too big into smaller pieces. You continue breaking pieces into smaller pieces until you have a detailed list of the steps you need to perform to solve the original problem. As you break a task into smaller pieces, you should be on the lookout for opportunities to save some work. If you notice that you're performing some chores more than once (perhaps while describing multiple main tasks), you should think about pulling that chore out and putting it in a separate method. Then all the tasks can use the same method. That not only lets you skip writing the same code a bunch of times, it also lets you invest extra time testing and debugging the common code while still saving time overall.

If the main task's description becomes too long, you should break it into shorter connected tasks, or use-case scenarios. For example, suppose you need to write a method that searches a customer database for people who might be interested in golf equipment sales. You identify several dozen tests that identify likely prospects: people who earn more than $50,000 per year, people who live near golf courses, country club members, people who wear plaid shorts and sandals with spikes, and so forth. If the list of tests is too long, it will be hard to read the full list of steps required to perform the original task. In that case, you should pull the tests out, place them in a new task described on a separate sheet of paper (or possibly several), and refer to the new task as a subtask of the original.

For example, suppose the original method is called PromoteSale. Originally, its description might look like this:

PromoteSale() 1. Identify customers who are likely to buy items on sale and send them e-mails, flyers, or text messages as appropriate.Now add some detail.

PromoteSale()

1. For each customer:

A. If the customer is likely to buy:

i. Send e-mail, flyer, or text message depending on the customer's preferences

Step A "If the customer is likely to buy" will be pretty long, so create a new

IsCustomerLikelyToBuy method. Similarly, step i will be fairly complicated, so create a new

SendSaleInfo method. Now the main task looks like the following.

PromoteSale()

1. For each customer:

A. If IsCustomerIsLikelyToBuy()

i. SendSaleInfo()

At this point, you need to write the IsCustomerLikelyToBuy and SendSaleInfo methods. Here's

the IsCustomerLikelyToBuy method.

IsCustomerLikelyToBuy() 1. If (customer earns more than $50,000) return true . 2. If (customer lives within 1 mile of a golf course) return true . 3. If (customer is a country club member) return true. 4. If (customer wears plaid shorts and sandals with spikes) return true . ... 73. If (none of the earlier was satisfied) return false .Here's the SendSaleInfo method.

SendSaleInfo() 1. If (customer prefers e-mail) send e-mail message. 2. If (customer prefers snail-mail) send flyer. 3. If (customer prefers text messages) send text message.You can add other contact methods such as voicemail, telegraph, or carrier pigeon if appropriate. This version of the SendSaleInfo method may also need some elaboration to explain how to determine which contact method the customer prefers.

SendSaleInfo() 1. Use the customer's CustomerId to look up the customer in the database's Customers table. 2. Get the customer's PreferredContactMethod value from the database record. 3. If (customer prefers e-mail) send e-mail message. 4. If (customer prefers snail-mail) send flyer. 5. If (customer prefers text messages) send text message.Continue performing rounds of refinement, providing more detail for any steps that aren't painfully obvious, until the instructions are so detailed a fifth-grader could follow them. At that point, sit down and write the code. If you've reached a sufficient level of detail, translating your instructions into code should be a mostly mechanical process.

Top-down design gives you a way to turn a task statement into code, but there are still a lot of tricks you can use to make writing code faster and easier. Other tips make it easier to test code, debug it when a problem surfaces, and maintain the code in the long term.

Writing good code can be difficult. To know if you're writing the code correctly, you need to completely understand what you're trying to do, what the code actually does, and what could go wrong. You need to know in what situations the code might execute and how those situations could mess up your carefully laid plan. You need to ask yourself, what if an important file is locked, a needed value isn't found in a parameter table, or if a user can't remember his password. Keeping everything straight can be quite a challenge. You can make your life a little easier if you write code only while you're wide awake and alert.

Most people have certain times of day when they're most alert. Some people are natural morning people and work best in the morning. Others work better in the afternoon. Some programmers do their best work after midnight when the rest of the world is asleep. Figure out when your most effective hours are and plan to write code then. Fill out progress reports and timesheets during less productive hours.

The computer doesn't read your code. Depending on your programming language and development environment, your code must be translated one, two, or more times before the computer can read it. All the computer sees is a string of 0s and 1s (machine language). The reason you write code in some higher-level programming language is that 0s and 1s are confusing for you. Using a higher-level language lets you tell the computer what to do in a way that you can understand. Later, when your application is doing something wrong, it lets you trace through the execution to see what the computer is doing and why.

Debugging and maintaining code is far more difficult and time-consuming than writing code in the first place. The main reason is because you know what you are trying to do when you write code. Later when you're called upon to debug it, you might not remember exactly what the code is supposed to do. That makes it harder to identify the difference between what the code is supposed to do and what it actually does, so it's harder to fix. To make debugging and maintaining code easier, you need to write code that is clear and easy to understand.

There are a few things that most programmers instinctively avoid because they don't feel like they're part of writing code. One of those is writing comments. Many programmers use one of two models for writing comments. The first approach is to write comments as you code. You write a loop and then put a comment on top of it. Later you realize that the loop isn't quite right, so you change it and then update the comment. The second strategy is to write all the code without comments. When you're finished with your revisions, you go back and insert the bare minimum number of comments that you think you can get away with.

In both of these scenarios, the problem isn't that you have too many comments. The real problem is that you're trying to write comments to explain what the code does and not what it should do . When you tweak the code, you change what it does, so you need to update the comment. That creates a lot of work and that makes programmers reluctant to write comments. If the code is well-written, the future reader will read the code to see what it actually does. What that person needs is comments to explain what the program is supposed to do. Then debugging becomes an exercise in determining where the program isn't doing what it's supposed to be doing.

One way to write comments that explain what the program is supposed to be doing is to write the comments first. That lets you focus on the intent of the code and not get distracted by whatever code is sitting actually there in front of you. It also means you don't need to revise the comment a dozen times. The code itself might change a dozen times, but the intent of the code better not! If it does, then you didn't do enough planning in the high-level and low-level design phases.

For example, consider the following C# code.

// Loop through the items in the "items" array.

for (int i = 0; i < items.Length - 1; i++)

{

// Pick a random spot j in the array.

int j = rand.Next(i, items.Length);

// Save item i in a temporary variable.

int temp = items[i];

// Copy j into i.

items[i] = items[j];

// Copy temp into position k.

items[j] = temp;

}

The comments in this code explain what the code is doing, but they're mostly redundant.

The comments are just English versions of the programming statements that follow.

From a stylistic point of view, the comments are also distracting. They break up the visual flow and

make the code look cluttered and busy.

Now that you've read the code, ask yourself, "What does it do?" It's kind of hard to tell because the comments don't actually tell you what the code is supposed to do. Now consider the following version of the code:

// Randomize the array.

// For each spot in the array, pick a random item and swap it into that spot.

for (int i = 0; i < items.Length - 1; i++)

{

int j = rand.Next(i, items.Length);

int temp = items[i];

items[i] = items[j];

items[j] = temp;

}

In this version, the comments tell you what the code is supposed to do, not what it actually does.

The first comment gives the code's goal. The second comment tells how the code does it.

After you read the comments, you can read the code to see if it does what it's supposed to do. If you think there's a bug, you can step through the code in the debugger to see if it works as advertised. This code is less cluttered and easier to read. It doesn't contain redundant comments that are just English versions of the code statements. These comments also don't need to be revised if the developer had to modify the code while writing it.

In addition to writing good comments, you can make the code easier to read if you make the code self-documenting. Use descriptive names for classes, methods, properties, variables, and anything else you possibly can. One exception to this rule is looping variables. Programmers often loop through a set of values and they use looping variables with catchy names like i or j . That's such a common practice that any programmer should be able to figure out what the variable means even though it doesn't have a descriptive name.

You can also make your code easier to understand if you don't use magic numbers. (A magic number is a value that just appears in the code with no explanation). Instead of using a magic number, use a named constant that has the same value. Better still, if your language supports enumerated types, use them. They also give names to magic numbers and some development environments can use them to enforce type rules.

Write code in small pieces. Long pieces of code are harder to read. They require you to keep more information in your head at one time. They also require you to remember what was going on at the beginning of the code when you're reading statements much later.

If a piece of code becomes too long, break it into smaller pieces. Exactly how long is "too long" varies depending on what you're doing. Many developers used to break up methods that didn't fit on a one-page printout. A more recent tree-friendly rule of thumb is to break up a method if it won't fit on your computer's screen all at one time.

Each class should represent a single concept that's intuitively easy to understand. If you can't describe a class in a single sentence, then it's probably trying to do too much, and you should consider splitting it into several related classes.

Just as a class should represent a single intuitive concept, a method should have a single clear purpose. Don't write methods that perform multiple unrelated tasks. Don't write a method called PrintSalesReportAndFetchStockPrices. The name might be nicely descriptive, but it's also cumbersome, so it's a hint that the method might not have a single clear purpose. Even if two tasks are related, it's often better to put them in separate methods so that you can invoke them separately if necessary.

A side effect is an unexpected result of a method call. For example, suppose you write a ValidateLogin method that checks a username and password in the database to see if the combination is valid. Oh, and by the way, it also leaves the application connected to the database. Leaving the database open is a side effect that isn't obvious from the name of the ValidateLogin method. Side effects prevent a programmer from completely understanding what the application is doing. Because understanding the code is critical to producing high-quality results, avoid writing methods with side effects.

Sometimes, a method may need to perform some action that is secondary to its main purpose, such as opening the database before checking a username/password pair. There are several ways you can remove the hidden side effects.

First, you can make the side effect explicit in the method's name. For example, you could call this method OpenDatabaseAndLogin. That's not an ideal solution because the method isn't performing one well-focused task, but it's better than having unexpected side effects. (Any time you have "And" or "Or" in a method name, you may be trying to make the method do too much.)

Second, the ValidateLogin method could close the database before it returns. That removes the hidden side effect; although it may reduce performance because you may want the database to be open for use by other methods.

Third, you could move the database opening code into a new method called OpenDatabase. The program would need to call OpenDatabase separately before it called ValidateLogin, but the process would not be easy to understand.

Fourth, you could create an OpenDatabase method as before and make that method keep track of whether the database was already open. If the database is open, the method wouldn't open it again. Then you could make every method that needs the database (including ValidateLogin) call OpenDatabase. Methods such as ValidateLogin would encapsulate the call to OpenDatabase so you wouldn't need to think about it when you called ValidateLogin. There's still some extra work going on behind the scenes that you may not know about, but with this approach you don't need to keep track of whether the database is open or closed.

Murphy's law states, "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong." By that logic, you should always assume that your calculations will fail. To catch these problems as soon as possible, you should add validation code to your methods. The validation code should look for trouble all over the place. It should examine the input data to make sure it's correct, and it should verify that the result your code produces is right. It can even verify that calculations are proceeding correctly in the middle of the calculation.

The main tool for validating code is the assertion. An assertion is a statement about the program and its data that is supposed to be true. If it isn't, the assertion throws an exception to tell you that something is wrong. For example, suppose you're writing a method to list customer orders sorted by their total cost. When the method starts, you could assert that the list contains at least two orders. You could also loop through the list and assert that every order has a total cost greater than zero. After you sort the list, you could loop through the orders to verify that the cost of each order is at least as large as the cost of the one before it.

Most programming languages have a method for conditional compilation. By setting a variable or flipping a switch, you can indicate that certain parts of the code shouldn't be compiled into the executable result. For example, the following code shows some validation code in C#.

#if DEBUG_1 // Validate the sorted order data. . . . #endifThe code between the #if and #endif directives is compiled only if the debugging symbol DEBUG_1 is defined. If that symbol isn't defined, then the validation code is ignored by the compiler. You can use techniques such as this one to add tons of validation code to the application. While you are testing and debugging the application, you can define the symbol DEBUG_1 (and any other debugging symbols) so the testing code is compiled. When you're ready to release the program, you can remove the debugging symbols so that the program runs faster for the customers. Later, if you discover a bug, you can redefine the debugging symbols to restore the testing code to hunt for the bug.

Many companies insist you write code that tests whatever features you add to a product. These unit tests can be accomplished in two ways:

Code that demonstrates conditional compilation can be seen as follows:

Conversions.h,

Conversions.cpp,

General.h,

General.cpp,

Geometry.h,

Geometry.cpp,

Math.h,

Math.cpp,

Makefile.

Code that demonstrates the above with test cases can be seen as follows:

Conversions.h,

Conversions.cpp,

General.h,

General.cpp,

Geometry.h,

Geometry.cpp,

Math.h,

Math.cpp,

testCases.cpp,

Makefile.

The code with conditional compilation is suitable for developer level testing, but the code with test cases is much more suitable for unit-tests, in that test cases can be added and removed quite easily.

In SED505 (Design Patterns) we looked at the strategy design pattern. See week 6 of

Design Patterns.

Due to the modular nature of this design pattern, it is easy to add or remove test suites with this pattern. The example

that we can look at is the Combined Sorting Strategy. This code implements the strategy pattern to

choose one of five sorting strategies: sort, stable sort, partial sort, quick sort, and bubble sort.

The following code shows two executables: the Sorter and the Sorter_test. The Sorter

is the product per say, and the Sorter_test replaces the main function of Sorter with test suites.

As you can see, it is easy to add and subtract test suites. The user could be prompted to indicate which

test suites (s)he wishes to run as well:

SortingStrategy.h, abstract base class for sorting strategies,

StdSortStrategy.h, concrete sorting strategy using STL::sort,

StdStableSortStrategy.h, concrete sorting strategy using STL::stable_sort,

StdPartialSortStrategy.h, concrete sorting strategy using STL::partial_sort,

BubbleSort.h, concrete sorting strategy using BubbleSort,

QuickSort.h, concrete sorting strategy using QuickSort,

Sorter.h, context that uses a sorting strategy to sort data,

SorterMain.cpp, main function for sorting,

SorterMain_test.cpp, main function containing test suites for sorting,

Makefile, the Makefile.

The idea behind defensive programming is to make code work no matter what kind of garbage is passed into it for data. The code should work and produce some kind of result no matter what. For example, consider the following Factorial function written in C#.

public int Factorial(int number)

{

int result = 1;

for (int i = 2; i <= number; i++) result *= i;

return result;

}

This code works well in most cases. The code even works for strange values of the input

parameter number. If the parameter number is negative, the code also sets result to 1, the loop does nothing, and the

method returns 1.

In fact, due to a quirk in the way C# handles integer overflow, this method even returns a value

if number is really large. If number is 100, the loop causes result to overflow. The program sets

result equal to 0, ignores the overflow, and continues merrily crunching away. When it's finished, it

returns the value 0.

This is traditional defensive programming in action. No matter what value you pass into the

method, it continues running. It may not always return a meaningful result, but it doesn't crash

either.

Unfortunately this approach also hides errors. If the program is trying to calculate 100!, it's probably doing something wrong. A better approach is to make the Factorial method throw an exception if its input is invalid. That way you know something is wrong and you can fix it. This is called offensive programming. If something offends the code, it makes a big deal out of it. The following code shows an offensive version of the Factorial method:

public int Factorial(int number)

{

Debug.Assert(number >= 0);

checked

{

int result = 1;

for (int i = 2; i <= number; i++) result *= i;

return result;

}

}

The code begins with an assertion that verifies that the input parameter is at least 0.

The method includes the rest of its code in a checked block. The checked keyword tells C# to not

ignore integer overflow and throw an exception instead. That takes care of cases in which the input

parameter is too big.

If the program passes the new version of the Factorial function an invalid parameter, you'll know

about it right away so you can fix it.

When a method has a problem, there are a couple ways to tell the program that something's wrong. Two of the most common methods are throwing an exception and passing an error code back to the calling code. For example, the Factorial method shown in the previous section throws an exception if there's an error. The call to Debug.Assert throws an exception if its condition is false . The checked block throws an exception if the calculations cause integer overflow.

An exception interrupts the program's execution and forces the code to take action. If you don't have any error handling code in place, the program crashes. That means a lazy programmer can't ignore a possible exception. If a method such as Factorial might throw an exception, the code must be prepared to handle it somehow.

In contrast, suppose the Factorial method indicated an error by returning an error code. For example, when passed the number -300, it might return the value -1. The factorial of a number is never negative, so the value -1 would indicate there is a problem. The trouble with this approach is the program could ignore the error code. In that case, the program might end up displaying the bogus value -1 to the user or using that value in some other calculation. The result will be gibberish that is at best unhelpful and at worst misleading and confusing. On the other hand, an exception causes one to exit a function prematurely, without any clean up.

If you use assertions and exceptions to indicate errors, the code that calls your method needs to use exception handling to deal with those exceptions. One way to create better error handlers is to follow the same strategy you can use when writing comments and validation code: Do it first. When you start writing a method, paste in all the comments that you got from top-down design, add code to validate the inputs and verify the outputs, and then wrap error handling code around the whole thing. First, make the error handling code look for exceptions that you expect to happen occasionally and that you can do something about (like trying to open a locked file). Next, add code that looks for other expected exceptions about which you can't do anything except complain to the user. That code should restate any exceptions in terms the user can understand. For example, instead of telling the user, "Arithmetic operation resulted in an overflow," you can present a more meaningful message like, "All orders must include at least 1 item."

If you find that you're writing the same (or nearly the same) piece of code more than once, consider moving it into a separate method that you can call from multiple places. That obviously saves you the time needed to write the code more than once. More important, it lets you debug and maintain the code in a single place. Later if you need to modify the code for some reason, you need to make the change only in one method. If the code were duplicated, you would need to update it in every place it occurred. If you forgot to update it in one place, the different copies of the code would be out of synch and that can lead to some extremely confusing bugs.

One of my favorite rules of programming is:

First make it work. Then make it faster if necessary.Highly optimized code can be a lot of fun to write, but it can also be very confusing. That means it takes longer to write and test. It's also harder to read, so it's harder to debug and fix if there is a problem. Meanwhile, even the least optimized code is usually fast enough to get the job done.

To program as efficiently as possible, write code in the most straightforward way you can, even if it's not the fastest way you can imagine. After you get the code working, you can decide whether it is so slow that it requires optimization.

If you do discover that the program isn't running fast enough, take some time to determine where performance improvements will give you the most benefit. Typically 90 percent of a program's time is spent in 10 percent of the code. The program spends most of its time executing a small fraction of the code. Time you spend optimizing the 80 percent that's already fast enough is time that would be better spent on the slow 10 percent. Before you start ripping the code apart, use a profiler to see exactly where the problem code is. Then attack only the problem and not the whole program.

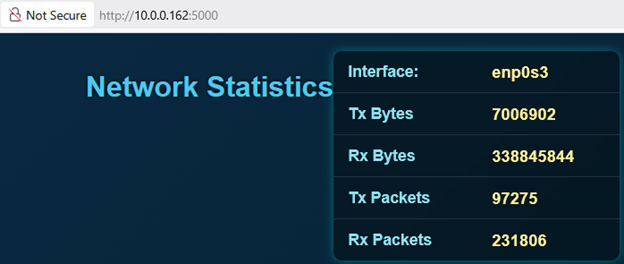

Back in SEP400 we looked at an interface

monitor which gathered information about a particular ethernet interface and dumped the statistics into a log file.

We now want the statistics from this interface monitor to appear nicely on a webpage, something looking like:

There is a front end to this problem (the webpage) and a backend (the interface monitor). How to make the two work together?

See Design Notes for a summary of the in-class discussion on possible approaches to

this design problem and the advantages and disadvantages of each.